Professor of History, Dr. Richard Spence who has previously contributed a very interesting (and highly relevant) blog on Jack Parsons was kind enough to again donate some previously unpublished content for your enjoyment.

The legend of Arthur Rochford Manby remains an enduring mystery of the American Southwest. A tale spilling over with tantalizing connections to black magic and the occult, murder, secret societies, foreign intelligence, artwork, and con-artistry — this fascinating report is a great fit for n01r.

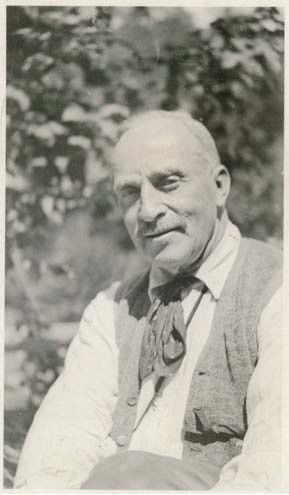

Who was this mysterious man?

Sagebrush Noir: The Life and Crimes of Arthur Rochford Manby

c. 2015

Dr. Richard B. Spence

On July 3rd, 1929 lawmen and townspeople crowded into a small room of a sprawling adobe mansion in Taos, New Mexico. Blue-bottle flies buzzed all around and the stench of death hung heavy in the air. The assembled gazed at a simple army cot where a half-dressed corpse lay wrapped in a blanket. And it was just a body: the severed, badly mutilated head rested in a nearby room. It was the general opinion then, and since, that the corpse and head belonged to the mansion’s owner, Arthur R. Manby. But others were not so sure. Most importantly, how had Manby died?

As word spread, Taos residents greeted it with a mixture of curiosity and relief. Many were quietly pleased, some openly delighted. Few, if any, mourned the departed. Since his arrival in the picturesque community in the 1890s, Manby had made himself one of its most prominent citizens and simultaneously one of its most feared and hated. Writer Jim Brandon aptly described Manby as “an odd amalgam of cultivated English gentleman, secret society adept and vicious robber baron” (Brandon, 149). He was all that and more. For almost thirty years Arthur Manby cast a dark shadow over Taos in an almost maniacal effort to make himself master of the land and the people on it.

A common element in the subsequent Manby legend was that he was the black sheep of an aristocratic English family cast out into the wilds of America with a small remittance and a promise that he would never return (Peters, 9). None of this was true, save that Manby was English. His family never abandoned him and rallied to his defense, even in death.

Arthur Rochford Manby was born in 1859, the second youngest of nine children of Edward Francis and Emily Morton Manby of Morecambe, Yorkshire. Francis came from a line of churchmen and military officers and was the rector of a parish which gave him the status of a minor country squire, though hardly an aristocrat. Upon his death in 1876, most of his modest estate went to the eldest son, Eardley, which doubtless influenced Arthur and three of his brothers to seek their fortunes across the Atlantic.

According to the family, Manby took a fall as a youth that resulted in a serious concussion and an altered personality. In place of a previously sociable, even-tempered lad there emerged a brooding character with a hair-trigger temper. This isn’t to say that Arthur Manby couldn’t be charming. Indeed, his future success as a con-man depended on that, even if his charm often resembled a snake hypnotizing its prey. Manby convincingly projected the image of a cultivated English gentleman. He was decently educated, surprisingly well read and able to converse intelligently on everything from art and music to criminology and Aztec mythology.

Art maven Mabel Dodge Luhan, who knew Manby in his last years, was enthralled by his voice and impressed by his knowledge, even while regarding him as repellent, hateful, and probably insane. And Manby was a bit of an artist himself. Like his mother, he dabbled in painting. Working on his watercolors was one of the few things that seemed to sooth his tortured spirit.

Arthur Manby arrived in northern New Mexico Territory in 1883. A Raton paper described him and two British companions as “men of large means seeking ranches, ranges, and cattle to invest in” (Peters, 20). This brings up a question that would whirl around Manby and his affairs for the rest of his life: was he an independent fortune hunter or the cat’s paw of other, more powerful persons who preferred to stay in the background? It was not uncommon for financial interests in London and elsewhere to employ ambitious and adventurous young men as agents to sniff out investments and buy up properties.

It is also an interesting coincidence, if no more, that Manby’s arrival in New Mexico coincided with the like activity of a certain Z. Z. Zacharoff-Williamson in neighboring Texas. Zacharoff, who would later reinvent himself as Sir Basil Zaharoff, mystery man of Europe and arms dealer extraordinaire, speculated in land and railroads with the secret backing of London money men like the Earl of Aylesford (Spence, “Zaharoff”). So was Manby another of Aylesford’s factotums?

By the end of 1883, Arthur, joined by his brothers, Alfred and Jocelyn, had established a small ranch west of Raton. Their spread was part of the Maxwell Grant, and that requires a little explanation. The Maxwell was an immense tract with its origins in the confusing and often contentious land grants handed out by the Spanish Crown in centuries past. Shortly before the Manbys arrived, the Maxwell was acquired, some might argue stolen, by a cabal of shadowy English investors who operated behind the Maxwell Land Grant and Railroad Company. They confronted a problem in the scores of small ranchers and farmers who inhabited the huge grant and who believed the land rightfully belonged to them. One of the most outspoken of these, and a lawyer no less, was Dan Griffin. His ranch directly adjoined the Manbys’. Griffin was convinced, and probably rightly so, that these aloof, tenderfoot Brits were part of the Company’s plan to drive him and other “squatters” off the Grant. A few months later, Dan Griffin was dead, shot to death by none other than Arthur Manby who naturally claimed self-defense.

Here the story gets more complicated. Also keenly interested in the Maxwell Grant was the so-called Santa Fe Ring. This was a cabal which dominated the politics, legal system and finances of Territorial New Mexico. The Ring worked hand in glove with the Maxwell Company and provided one of its legal eagles to defend Manby of the murder charge. With such help, Manby went scot-free, but he was forever remembered as the man who murdered Dan Griffin.

While his murder trial was pending, Manby joined another Maxwell Company gambit, “Masterson’s Militia.” Duly constituted by the territorial governor, these glorified gun-thugs aimed to settle political scores and forcibly evict “squatters” from the Grant. It all came to an inglorious end, and Manby narrowly avoided being kicked out of New Mexico along with the rest of Masterson’s gang. It remained, however, another black mark on his reputation.

After the Masterson fiasco, Arthur and his brothers went their separate ways and he abandoned ranching for mining, or rather acquiring mining claims. In 1891, he crossed the snow-crested Sangre de Cristo Mountains into the Taos Valley. To him, it was a Garden of Eden and his desire to possess it would dominate the rest of his days. Manby was neither the first not the last outsider to be mesmerized by the place. Artists and writers such as Georgia O’Keefe, D. H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley found inspiration here, as did psychoanalyst Carl Jung who saw in Taos a manifestation of the fabled Magic Mountain. Near the turn of the 20th century, Taos and its environs was an isolated community largely populated by the indigenous Pueblos and Hispanos, the descendants of Spanish colonists who had settled in the area in the 17th and 18th centuries. Anglos, like Manby, were a distinct minority and local culture included a powerful mixture of Native magic and Iberian sorcery, or brujeria.

One of the most important, if largely invisible, institutions in the area was Los Hermanidad de Nuestro Padre Jesus, also known as Los Hermanos de Luz, Los Hermanos Penitentes or simply the Penitentes. They were the survival of a 16th century Spanish lay order of penitents and flagellants who were known for carrying out mock (or not so mock) crucifixions each Easter. But their influence went far beyond that. The Penitentes formed a kind of Hispano freemasonry, a secret society that subtly influenced or even controlled many aspects of local life (Brandon, 150-151).

Also active in northern New Mexico in the 1890s were Las Gorras Blancas (“White Caps”) a largely Hispano society of hooded, night-riding vigilantes who waged a campaign of sabotage and intimidation against the encroachment of the railroads, big ranchers and land-grabbing newcomers like Arthur Manby. Many suspected they were just the political action wing of the Penitentes.

Manby soon discovered that lands around Taos were part of another murky land grant, the Antonio Martinez. The sheer scenic beauty of this “Egypt of New Mexico,” its fertile soil, abundant water and mineral wealth locked in the surrounding hills, plus therapeutic springs deep in the chasm of the Rio Grande, made visions of empire swim in his head (U. S. Congress).

Still, it’s again fair to ask if Manby’s interest in the grant was entirely personal, or whether he was an agent acting for others. For one thing, the Martinez Grant sat astride a proposed route for the Cimarron and Taos Valley Railroad (Ibid). The grant also controlled access to a sizable stretch of upper Rio Grande watershed. It’s probably not a coincidence that during the 1890s, a powerful British consortium took a keen interest in the river and its life-giving water. The group included Samuel Hope Morley, a director of the Bank of England, along with well-heeled investors like the Earl of Winchelsea and Nottingham, Baron Clanmorris and Lord Ernest Hamilton (Anderson). When their plans dried up, so did most of Manby’s financial backing.

Through his interest in mining, Manby formed a partnership with a pair of dubious locals, Columbus Ferguson and Bill Wilkerson (sometimes Wilkinson). They had a stake in some diggings on nearby Baldy Mountain, most notably the Mystic Mine, a place that has an especially sinister reputation in the Manby saga. The Mystic, to the extent it ever produced gold at all, was long since played out. But it lay in close proximity to the rich Aztec Mine, a fact that Manby and his partners exploited to advantage. In addition to working their own claims, Ferguson and Wilkerson had reputations as “high-graders,” men who stole nuggets and ore from other mines. Pilferage from the Aztec and other diggings allowed Manby and friends to “salt” the Mystic to make it a seemingly rich prospect for unwary investors. To make this work, however, they had to first dispose of another partner, one Stone, who apparently balked at robbery and fraud. One day Stone’s decapitated body turned up near the Mystic. The murder was never solved and Manby took his place among the mine’s owners. Stone’s was but the first of many deaths and disappearances to follow.

Wilkerson would also later vanish under mysterious circumstances, but Manby’s relationship with Ferguson was to be a long and important one. Ferguson, a Union Army veteran originally from Illinois, drifted into Taos years early and married a girl from the local Medina clan. Through his wife, Ferguson had connections to the Hispano community and the Penitentes. The Ferguson’s had a pair of young daughters. One of them, Lucy, better known as Terecita, would forge an intimate and fateful relationship with Manby. He first took notice of her in 1902, when she was a blossoming, dark-eyed fourteen-year-old.

Despite their nearly thirty-year age difference, Manby was, literally or figuratively, enchanted. Terecita was beautiful and sensual and possessed a feral cunning Manby could appreciate. She claimed to have been kidnapped by gypsies as a child and taught to tell fortunes. Reading the lines in the Englishman’s palm, she claimed to see great things in store for him—and her (Peters, 97). She became well versed in local “magic,” including herbal cures—and poisons. Manby would find her talents useful in many ways. He dubbed her his “princessa” and she became his mistress. Though she and the Englishman would go on to marry others, their special relationship would endure right up to his death.

In the meantime, Manby had other business to attend to. In 1895, having established himself in Taos, he returned to England to confer with brother Eardley and the London “investors.” He had more meetings in New York going and coming. Unnamed “parties back East” would play a big part in his future dealings (Peters, 60). Many other trips followed to Philadelphia, St. Louis, Minneapolis and elsewhere. During 1900-01 he disappeared from Taos for almost a year and a half and spent most of the time, so he claimed, in Mexico.

The Mexican interlude may hint at Manby’s wider connections. He picked up some mining properties in Chihuahua where British concerns were active. But his sojourn south of the Border also coincided with the establishment of the Mexican petroleum industry which involved intense rivalry among competing American and British interests. The latter, spearheaded by the redoubtable Weetman Pearson (later Lord Cowdray), ultimately came out on top. Just what part, if any, Manby played in this business, is impossible to say, though his experience as ruthless acquisition agent might have come in handy.

It’s worth noting that Manby’s time in Mexico was roughly contemporaneous with another wandering Englishman, infamous Aleister Crowley. His purposes, ostensibly, were recreation and spiritual enlightenment, though it’s likely he also was engaged in some confidential work for His Majesty’s Government (Spence, Secret, 31-32).

This raises the question of whether Arthur Manby likewise had some connection to “British intelligence,” which was never absent anywhere London’s imperial and financial interests were concerned. Manby obtained American citizenship in 1899, though he made it plain that this was purely for business reasons. He retained a staunch loyalty to the Crown and Empire.

He joined the Patriotic League of Britons Overseas and may also have belonged to the paramilitary Legion of Frontiersmen. The latter openly billed itself as a “field-intelligence” force and was subsidized from the Secret Service budget (Records). In 1908, for instance, an LOF member in Butte, Montana wrote the organization’s leader, Roger Pocock, asking help in recruiting men “who can be absolutely relied upon for silence, courage and squareness, [and] who would be prepared to work against any country for the money that would be in it…and will be left alone to work in their own way”(Ibid). Save for the “squareness” part, this fit Manby to a “T.”

While Manby assumed a prominent role in Taos, he made little effort to ingratiate himself with the locals. With the exception of a few individuals, most notably ‘Princess’ Terecita, he held both Anglo and Hispano residents in open contempt (Manby, incidentally, spoke fluent Spanish). The Indians he detested but also feared. He heard the same tales of mysterious native rites that fascinated Jung, such as a cave near Frijoles Canyon “where human sacrifices were made by the Indians in bygone years—some say even now” (Brandon, 148). He doubtless rode past La Madera “where the witches live in caves and little huts up and down the mountain valleys, like some weirdly transposed Tibetan Bon sorcerers.” (Ibid.) Maybe these gave him ideas of his own.

Manby cultivated his air of mystery by keeping to himself. He was most often encountered riding his black stallion, accompanied by one or two big, unfriendly dogs and armed to the teeth. The precautions weren’t just cosmetic; he had made plenty of enemies. Few of the people living on the Martinez Grant possessed formal deeds to their property, a fact Manby ruthlessly exploited. When he could not buy them out for cheap or bully them into leaving, Manby searched delinquent tax records to buy up properties and evict their unlucky residents. A local businessman who accepted Manby’s financial “help” ended up bilked out of everything he owned and saw his family tossed into the street (Waters 87-90).

Manby’s reputation for unscrupulous business tactics was compounded by his vindictiveness and explosive temper. A local newspaper editor, Jose Montaner, openly criticized the Englishman’s unsavory practices. Manby naturally took offense and spying Montaner sitting in a Taos café, he burst into the place, struck Montaner from behind and would have stabbed him with a dinner knife before a friend felled the enraged Manby with a chair. He neither apologized for the assault nor suffered any serious legal complication. The point was made: Arthur Manby was someone you did not cross.

Through hook and crook, by 1905 Manby had rounded up sufficient holdings to form the Taos Valley Land Co., the first of many shell corporations he would create to manage his empire, real and imaginary. He continued to suck in well-heeled investors, among them Chicago businessman Charles R. Hill, Michigan political boss Schuyler Olds and the wealthy Prescott family from Maryland. Manby’s “marks” weren’t innocent rubes but canny businessmen which makes his ability to bamboozle them all the more remarkable. To rope in the Prescotts, in 1907 the 48-year-old Manby married their 17-year-old daughter, Edith, affectionately called “Pinky.” The union was a disaster. After less than a year of marriage, during which she gave birth to a stillborn daughter, Pinky fled Manby’s gloomy adobe and filed for divorce on the grounds of “extreme cruelty” (Peters, 88). Manby took it all in stride; he had what he really wanted, the Prescott’s money.

And, of course, the land, always the land. In May 1913, the day he had dreamed of for nearly twenty years finally arrived. After lengthy study, much legal maneuvering and doubtless intimidation and bribery, a court referee awarded Arthur Manby title to the entire Martinez Grant. He was on the top of the world. The reality was that his empire was a fragile house of cards. Manby begged, borrowed and stole every dollar he could to get hold of the land, but he still needed capital to develop it. One setback was the abandonment of any further plans to run track through the Taos Valley.

But Manby was also undone by his own greed. He had a simple approach to debts or other financial obligations; he refused to pay them, including alimony to his ex-wife. He tried to stay afloat by selling off small tracts of the Martinez and mortgaging others, and kept creditors a bay by shuffling assets and debts between his numerous front companies. Nevertheless, the day of reckoning finally arrived. In June 1916, barely three years after his great victory, another court ordered the Martinez lands to be sold at auction. Manby stalled for a few more years, but in the end all he was left with was his mansion, a measly two dozen acres and his mines.

An interesting but little examined question is who ended up with the Martinez Grant when it slipped from Manby’s hands. By 1921, the grant’s title belonged to the so-called Watson Land Company. The ostensible head and chief stockholder was Charles A. Watson, a wealthy merchant from Chicago. Back in 1909, Watson and Manby, along with another Chicagoan, Charles Hyron Hill, had incorporated the Taos Land Co. and its kindred Taos Irrigation Co. with combined capital of $1,300,000. Also involved in these dealings was Santa Fe lawyer George M. Neel, formerly of New York City (U. S. Census). Was he an agent for the mysterious “parties back East” or was the Santa Fe Ring still alive and up to its old tricks?

Manby’s troubles coincided with another event, little noticed amidst the bigger drama, but probably not unrelated. This was the sudden disappearance of his old partner in high-grading, Wilkerson. Those who took notice suspected Wilkerson had departed the mortal realm at Manby’s instigation. Had the Englishman tied-up a dangerous loose end, or had Wilkerson sold out Manby and fled?

In his desperate effort to raise cash, Manby almost got himself another wife. A few years earlier he had run into Margaret Waddell, a wealthy Los Angeles woman, at a Texas spa. She later visited Santa Fe and Manby, turning on the charm, persuaded her to loan him money against a painting he insisted was a genuine Van Eyck. He also seems to have convinced her that they would wed. But Margaret was no love-sick fool. She showed the painting to experts who branded it a fake. In 1915, she hit Manby with a breach of promise suit. Manby, as usual, ignored it and the subsequent judgment against him.

Manby’s romancing of Waddell, and other women, did not sit well with Princess Terecita, his mistress and valued co-conspirator. Manby purchased a local tourist camp which he turned over to Terecita and her aging father, but he refused to make an honest woman of her, perhaps feeling the tainted Ferguson name could not be combined with his own. Terecita got revenge, of sorts, by marrying a local man, a humble farm hand, though she didn’t stop sharing Manby’s bed. She gave birth to several children, some of whom, it was assumed, were the Englishman’s. If so, he never acknowledged them.

Manby’s loss of the Grant left him embittered and increasingly paranoid, but by no means defeated. He claimed that a vast, dark conspiracy was out to destroy him and spent more and more of his time ensconced in his fortress-mansion where he adopted the habits of ritualistically unlocking and locking doors and sleeping in a different room each night. He stashed loaded weapons throughout the house and fear of poisoning made him cautious of what he ate and who prepared it. It’s easy to see such behavior as an elaborate act or a sign of creeping psychosis, but Manby’s fears may not have been altogether imaginary.

It’s curious that the only census to record Manby’s presence in Taos, or in New Mexico, it that of 1920. He may have been too far out in the sticks to have been counted in 1890 and wandering around Mexico in 1900, but his absence in 1910 is harder to account for. Perhaps he didn’t want to be recorded. His 1920 entry reveals a few interesting details. He gave his profession as “farmer, manager” and shaved a few years off his age (U. S. Census). He also, for whatever reason, erroneously stated his year of naturalization as 1885. Overall, though, there is nothing in this simple accounting to differentiate him from many of his neighbors, nothing to indicate who and what he really was.

Around the same time, who should show up in town but Manby’s old pal Wilkerson. Not only was he very much alive but the once shabby miner was smartly dressed and flush with cash. The story pieced together was that Wilkerson had spent the last several years running Manby’s mines in Chihuahua which were used as cover to launder ore pilfered from the Aztec and other mines. What isn’t clear is what brought Wilkerson back to Taos. He wasn’t destined to be around for long. Years later, a onetime maid at Terecita’s tourist camp recalled seeing Wilkerson arrive one evening to be greeted by Manby, the Princesa and a local tough guy, Carmen Duran. The latter was Manby’s chief gun-thug as well as Terecita’s lover on the side. Later that night the terrified maid stumbled across Wilkerson’s dead body and watched as Manby and his accomplices carted it off to whereabouts unknown. The maid wisely kept her mouth shut. Had Wilkerson been murdered for his money, or to keep him quiet, or both? Did he try to shake-down Manby, or was it some other reason entirely?

In any case, the same woman definitely recollected that Wilkerson’s head was attached to his body when she last saw it. Not long after, old Columbus Ferguson, who had been in declining health, seemed to lose his wits and woke the camp “screaming something about Wilkerson’s head” (Waters, 168). With Manby’s help, Terecita had the old man committed. He later returned to her care, a muttering shell of a man, and shuffled off his mortal coil in 1927. Dutiful daughter Terecita may have helped her dear old daddy out of his misery. Maybe that gave her a few other ideas.

In the meantime, Manby hit on a new scheme; to fight the malicious conspiracy he would form one of his own. Thus was born “U. S. Secret and Civil Service Society, Self-Supporting Branch,” a secret society-cum-extortion racket that cast a dark shadow over Taos for most of the 1920s. In its creation Manby took inspiration from the Gorras Blancas, the Black Hand, the Ku Klux Klan and even the Penitentes. Its supposed quasi-official status may have been a nod to the Legion of Frontiersmen. The central conceit of the organization is that it was a secretly authorized auxiliary of the U. S. Government to maintain law and order and combat nefarious influences of all kinds. Most importantly, according to Manby, it battled relentless bands of gunmen sent by his enemies to rub him out and seize his remaining assets. Oddly, these pitched battles always seemed to happen out of sight and hearing of local residents.

At the head of the Society sat the triumvirate of Manby, Terecita and Carmen Duran, though most of its communiqués bore the signature of Severino Gutierrez, the name of a local miner who had disappeared years earlier. Manby masked his role by making Terecita the treasurer; all monies went to her, in theory at least. The basic tactic was to “invite” well-to-do members of the local community to join with the clear implication that refusal was not an option.

Once enlisted, new members learned what “Self-Supporting” meant. They received constant and urgent requests for money and when those wouldn’t suffice, deeds and mortgages were demanded. Manby promised that in return for their sacrifice and loyal service, the Government would lavish them with abundant reward. To make his point, he would flash “Million Dollar Gold Certificates” supposedly issued by the U. S. Treasury (Downard, 89). The certificates, presumably, were fakes since the Treasury never issued any of that denomination. Similar gold certificates have been connected to an alleged fortune in gold smuggled out of Mexico by the followers of the late dictator Porfirio Diaz (Downard, 90). Could that have anything to do with what Wilkerson had been up to South of the Border?

In the meantime, Manby’s minions had to pony up. They also discovered that once you were in the Society, there was no getting out, alive anyway. To make that point, Manby led recruits through a Masonic-style initiation in which he acted out the shooting, stomping and beheading that would befall anyone who betrayed his oath of obedience. He went through the motions of sending “secret messages” to Society members by semaphore or raising and lowering the flag in his garden. Perhaps strangest of all, he claimed to receive mysterious nocturnal visits from a marvelous airship, the “Garibaldi,” that came from Italy (Waters, 193). Did he mean to imply that he was somehow in cahoots with Mussolini or the Mafia, or was this some weird, early version of a UFO tale?

Manby also took to calling himself the “Lenin of the West” with Terecita his “Rosa,” an apparent reference to murdered German Communist Rosa Luxemburg (Waters, 195). It was a strange sort of thing to come from a man like himself in this far-off corner of the American West. Was he being ironic, or did he actually see himself as some sort of sagebrush Bolshevik? If nothing else, it’s indication that he was knowledgeable of persons and international affairs that would seem to have no bearing on his own activities.

Taos resident Cecil Ross joined Manby’s outfit mostly to discover what it was really about. He figured out that the Society had its fingers in extortion, land fraud, robbery, and even murder for hire. Given that its activity played out against the backdrop of Prohibition, it must have been involved in bootlegging too. There was a brisk business in smuggling booze over the border and Manby’s Mexican operations would have come in very handy. Ross recalled one night accompanying Duran and others to a meeting with Manby at the entrance to the Mystic mine. The Englishman received them seated near a blazing fire before which there was a carefully arranged human skull and crossbones, symbols which again evoked Masonic and Penitente rituals. Inside the mine, Ross could see a kind of alter with candles and a box full of rattlesnakes (Waters, 199). The tableau was intended to intimidate, and it did.

The episode brings up the question of to what degree occult practices influenced Manby, either for effect or from actual devotion. Manby was reputedly superstitious and possessed by vivid fears, real or imaginary. Thus, it’s not hard to imagine him seeking protection in any way he could, including the supernatural. As noted, the American Southwest had a deep-rooted tradition of magic for which Taos was—and is– a kind of Mecca. Manby’s acquaintance with Mexico and his fascination with Aztec legendary may also have played a role. Decapitation, often with ritual overtones, is a sinister leitmotif in Manby’s story and echoes legends of the Mesoamerican bat-god Camazotz and his penchant for nipping off heads. Ritualistic beheadings today play an important part in the internal mysticism of Mexican drug cartels, much of it linked to the syncretic folk cult of Santa Muerte (“Saint Death”) (Bunker).

The belief is that through such grisly acts of devotion, the individual or gang will gain protection from enemies and prosper in its criminal endeavors. What more could Arthur Manby have wanted?

There is also a theory that Manby’s secret society was created as a direct challenge to the power of the Penitentes, a group that the Englishman believed was one of the sources of his difficulty. Evidence for this rests on the supposed fact than his Secret Service included “many Anglo-Protestants and Masons who joined to oppose the secret sect of the Spanish Penitentes” (Waters, 243). Some even believed that vengeful Penitente Brothers were behind his murder. The fact was a lot of people wanted Arthur Manby dead.

One person who may shed some light on Manby’s more arcane associations is James Shelby Downard, though it’s a big maybe. To label Downard a conspiracy theorist hardly does him justice. Depending on one’s point of view, he was either a pioneering investigator of the dark heart of American society or a crackpot with a vivid imagination and extreme delusions of persecution. Downard twice references Manby in his autobiographical The Carnivals of Life and Death. This purports to chronicle Downard’s childhood battles against the malign forces of “Masonic-sorcery” which, for reasons never entirely clear, were out to get him. As bizarre as Downard’s tale is, almost all the people and places he mentions were real, Manby and Taos included.

According to Downard’s story, he first heard of “Monster Manby” in 1919 when he and his mother and a mysterious “Count” took a road-trip across the southern U.S. One of their early stops was Jekyll Island, Georgia, home to the Jekyll Island Club, the exclusive and very private getaway of America’s financial elite. While there, Downard claimed to have witnessed a peculiar Masonic “face-off” ritual which he would see repeated years later in Taos. Leaving Georgia, Downard’s little band paid a visit to Sugar Loaf Key in Florida. This may be of some significance because Downard mentions a local luminary named R. C. Perky. The latter was a Manby-esque entrepreneur and land developer perhaps best remembered for building the “Perky bat tower.” This was supposed to attract bats to fertilize local fruit trees, but in the view of “certain occultists” the tower was really a thinly-disguised shrine to the aforementioned bat-deity Camazotz and Perky, one of its devotees (Brandon, 65-66)!

So, was Manby another? Downard’s party next headed West and ended up in Columbus, New Mexico where little James Shelby found himself abandoned by mom and the Count. When she later turned up, she explained that she has been held captive “by a powerful man named Manby in Taos” who was “the head of a secret society and everyone was scared of him” (Downard, 36).

Downard next encountered Manby, this time in person, in 1925. In the company of a family friend, young Downard again bore witness to the ritual “face-off,” this time between the friend and Manby. The two men engaged in a prolonged stare-down while brandishing phony “Million Dollar Gold Certificates” at each other (Downard, 90). The Englishman, in Downard’s estimation, was a “Masonic conman who hoodwinked many people into believing that queer money was good” (Downard, 89). Most curious of all, perhaps, Downard acknowledges Manby’s reported death and decapitation in 1929, yet inexplicably insists that he really died soon after he met him in 1925 (Downard, 90). This isn’t just Downard’s mistake; Manby’s death is frequently given as 1926, though official records are quite definite that it was 1929 (Taos). Overall, Downard’s portrait of Manby seems a conglomeration of muddled fact and creative imagination. Nevertheless, perhaps Downard’s observation that “Sorcerers often die of decapitation” should not be dismissed too lightly (Downard, 91).

Besides Downard, there is another, documentable connection between Manby and the Olympians of the Jekyll Island Club. This was Dr. Victor Corse Thorne, a Club member, East Coast Brahmin and a man who maintained regular correspondence and dealings with Manby during the last decade of his life (Thorne). Manby met Thorne through a mutual acquaintance, Charles Lambert, a wealthy Philadelphian who owned a big spread near Maxwell. A physician turned Wall Street lawyer, Thorne’s New England Quaker forbearers had made a fortune in coal mines and Victor sought to expand it. His interest in a Wild West schemer like Manby is hard to explain. What initially drew them together were Manby’s small art collection and his desire to sell or mortgage the paintings for cash. The provenance and authenticity of most was dubious and Thorne was too experienced to be duped easily. The Englishman, however, couldn’t resist trying to lure deep pockets Thorne into a bigger scheme.

One of few properties Many had left was a thermal spring which lay about a dozen miles north of Taos at the bottom of the steep Rio Grande gorge. The spot is still commonly referred to as Manby Hot Springs. The steaming pools were well known to the local Indians who had carved petro glyphs into the surrounding rocks. Manby believed that these markings and nearby ruins identified the spot as the mythical homeland of the Aztecs, Aztlan, and that the waters possessed miraculous powers of healing and rejuvenation. It’s the same hot spring Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper frolic in in Easy Rider.

Manby built a small stone bathhouse over the springs to keep out the riffraff and as a kind of personal sanctum. In 1922, he presented Thorne with an elaborate prospectus for the development of the springs into a full-blown resort, a scheme he believed would further enrich the good Doctor and restore his own fortunes. The report included a detailed chemical analysis of the spring water which, according to Manby’s calculation, included a significant amount of “radioactive” elements (Waters, 178-179 and 185-188). This may be an important clue to his relationship with Thorne. The latter’s holdings included the Denver-based Radium Company. The quest for radioactive elements was in its infancy and natural springs were seen as an exploitable source. Thorne hoped to corner the American market in hard-to-find radium and Manby may have been trying to help him. The catch was that Manby didn’t really own the springs. When their absentee owner rejected his offer to buy, the Englishmen simply moved in and took over. Thus he became one of the very squatters he so much despised.

The most interesting question in the Manby-Thorne partnership is who was conning who. The Doctor advance Manby several loans in the sums of a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, but he was clever enough to demand collateral for each. Thus, upon Manby’s death, and to the dismay of Terecita and others, Thorne held lawful title to just about everything Manby owned: land, house, furnishings and paintings. More than anyone else, Thorne directly benefitted from Arthur Manby’s demise.

In the meantime, as Cecil Ross learned more about the Secret Society’s inner workings, he began to wonder just how much Manby was really in control. One disturbing piece of evidence was a memo that outlined a scheme for gaining control of property in and around Taos. Among the indicated targets for acquisition was the Manby mansion, which made no sense if he was running the scheme. Was this all part of the mysterious agenda of the “higher-ups,” or was it the handiwork of his own beloved Princess Terecita?

As Manby himself discovered not long before his death, Terecita’s affections were not to be taken for granted. She was nearly forty, unmarried, with a brood of offspring, and the only tangible asset she had to show for her relationship with Manby was the dilapidated tourist camp. She was, in theory at least, the custodian of the ill-gotten gains of the Society, but that would never really be hers so long as the Englishman lived. She all too aware of the parade of young prostitutes who came and went, often in hysterics, from the mansion. As noted, she had found her own carnal diversion in the arms of Carmen Duran. Manby was beside himself with jealousy when he finally learned of their affair, and like a love-sick schoolboy he alternately blustered and begged for Terecita to come to him.

Arthur Manby was publicly seen alive for the last time on the evening of June 30th, 1929. He rode his horse back to the mansion apparently returning from Terecita’s. One person later recalled that the usually surly Brit seemed in an oddly chipper mood (Peters, 147). A subsequent reconstruction of events showed that the following day, July 1st, he received a note from Terecita saying she was ill and begging him to come to her. He presumably obeyed, though no one in town saw him leave or return. Terecita and Duran insisted that Manby visited her at the court, then left. They knew no more.

Two days passed. On the morning of the 3rd, a deputy U. S. Marshal arrived at Manby’s adobe. He carried court papers announcing a renewed breach-of-promise claim by Margaret Waddell. Though a court had awarded her $12,000 nearly ten years earlier, Manby never paid her a dime. The equally stubborn Waddell was making a fresh demand for settlement. It was odd timing to say the least. The marshal pounded on the courtyard gate, but there was no response. Warned about Manby’s dogs and their master’s ornery reputation, the Marshal decided not to enter on his own and went to the local sheriff for advice. The sheriff accompanied him back to the mansion, but in the short interval word had spread that Manby was dead. The source of this rumor, as it turned out, was George Ferguson, Terecita’s nephew. By the time the lawmen reached Manby’s house, a small crowd was milling around the gate. Among them were Terecita and Carmen Duran. After a brief debate as to how best to break in, Duran nonchalantly pulled keys from his pocket and unlocked the gate. He then boldly led the way into the house, where he unlocked more doors and headed straight to the bedroom where Manby’s body lay. He even petted and took charge of the Alsatian dog that was resting calmly next to the cot. The animal, it turned out, had been Duran’s before he gave it to Manby.

All this ought to have raised suspicions, yet neither Duran nor Terecita faced any questioning. Even more astounding, within an hour of the body’s discovery a hastily convened coroner’s jury issued a verdict of death by natural causes and had the remains buried. There was not even the pretense of an autopsy. Manby may have been dead, but the Society was still alive and it is hard not to see its influence behind these bizarre events. It’s also difficult not to suspect that Terecita and Duran were behind Manby’s demise. All the key ingredients were there: greed, jealously and betrayal, a murderous mix if there ever was one. Was Arthur Rochford Manby done in by the only person he loved and one of few he’d ever trusted?

Manby biographer James Peters comes to that conclusion, but adds a twist. He believes that the almost seventy-year-old Manby suffered from the ravages of tertiary syphilis (Peters, 127). It was killing him, but not fast enough to satisfy Princess Terecita who feared that the increasingly demented Englishman would blow the racket they had so carefully crafted. She may also have believed, erroneously as it turned out, that she would be the beneficiary of his estate. After all, he had sworn to always take care of her. Syphilis was indeed widespread in the area, particularly among the whores Manby was known to patronize. There is also evidence that he was being treated for the ailment, or something like it, by the town doctor. On the other hand, Manby was a hypochondriac and took medicines for all sorts of problems, real and imaginary. There is no evidence that Pinky or Terecita, both of whom lived to ripe old ages, contracted the disease. More importantly, there is also no convincing evidence that Manby was losing his mind or behaving more strangely. His correspondence with Thorne shows a mind that was not only rational, but also still crafty enough to conjure up grandiose plans.

But Manby’s death isn’t the end of the story. To most people it hardly mattered what or who had killed the odious Englishmen and they were content to let the matter rest. Some, however, had their doubts. The evident decay, they argued, was too advanced for a man dead only two days. Besides, wouldn’t a starving canine have gone for meat and viscera, not the head? And why did the animal take it into another room and then shut the door behind it? Some speculated the head was detached and given to the dog with the deliberate aim of destroying its features and rendering exact identification impossible. Others questioned whether the head really went with the body. Manby was a large man, and the skull seemed much too small (“Murder”). Was the corpse really Manby’s at all?

One who rejected the coroner’s verdict was Arthur’s brother, Alfred. He had letters from Arthur expressing fear for his life and virtually predicting that he would be murdered. Another brother, Eardley, badgered the British Embassy and New Mexico Governor R. C. Dillon to reopen the case, and finally succeeded. A new inquiry under seasoned detective Bill Martin arrived at radically different conclusions. A careful examination of body revealed that the head had been neatly severed, not chewed. This made Martin delve deeper into Manby’s twisted affairs which him to Baldy Mountain and the Mystic Mine. Nearby Martin discovered a skeleton and separate skull which turned out to be the remains of the long-missing Wilkerson. Was that the same skull Ross saw in front of the campfire? Further search of the vicinity turned up a secret cemetery or body dump containing the bones of at least seven other men, all decapitated (Wallace). Along with the skeletal remains were remnants of clothing and personal effects which allowed Martin to identify most of the victims. They turned out to be local men who had vanished over the years. All had some connection to Arthur Manby.

Martin also dug into Manby’s personal papers, including his diary. The latter revealed that the date of 28 September 1921 held an ominous significance to the Englishman and haunted him for the rest of his life. It turned out to be the day of Wilkerson’s murder. Did Manby see in that a foreshadowing of his own end? Martin also unearthed account books showing that Manby had promised Princess Terecita the utterly amazing sum of $827,000,000 as well as title to lands in Missouri worth a supposed $40,000,000! (“Murder”) Needless to say, no such funds were to be found and the Missouri property, if it ever existed, was long since sold or mortgaged to someone else. Manby, it seems, had be scamming his beloved too. Terecita claimed as much, insisting that while Manby had been kind to her and she held much affection for him, he also had cheated her out of all her money. It was another good reason to want a man dead.

Even so, Manby’s secret society had extorted tens of thousands of dollars not to mention the sums it raised from bootlegging, high-grading, robbery and other criminal activity. What became of it? There was no indication Terecita and Duran got their hands on it. This would fuel tales of a fabulous Manby Treasure, perhaps buried in his garden, hidden in a stash on Baldy Mountain, or cached in some Mexican safe deposit box.

Then there was the lingering question as to whether Manby was really dead. While Martin harbored no doubts that the body in the grave was his, others remained skeptical. There were recurrent reports of the Englishman being seen alive. One of the more credible came from a man who knew him well and swore that he saw Manby alive and well Ojinaga, Chihuahua two years after his supposed burial (Waters, 245). Other old acquaintances claimed to have run into him in Italy (spirited away on the Garibaldi?), and yet another theory held that he had gone back to England where he was sheltered by his family and, perhaps, the British Government. Some even suspected that Manby had simply assumed a new identity, that of Dr. Victor Thorne. This was based on the fact that, as noted, Thorne was legal heir to almost everything Manby possessed, including his mansion which was duly rename Thorne House. While he owned a significant chunk of downtown Taos and subsequently poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into the community, some found it suspicious that Thorne never appeared there, instead sending a female secretary to oversee matters. The Doctor most assuredly wasn’t Manby, but some still wondered if “there hadn’t been a closer relationship between Thorne and Manby than was known.” It remains a valid question (Waters, 253).

Martin’s investigation left him no doubt that Carmen Duran and Terecita Ferguson, probably with the assistance of nephew George, had murdered Manby. In his reconstruction of the crime, they lured him the camp that night where they drugged and then bludgeoned and suffocated him. The skull showed evidence of blunt force trauma. They then bundled up the corpse and carried it back to Manby’s house in the dead of night. They had no trouble with access since they had keys to everything. When they cut off the head was uncertain, but Duran gave it to the dog perhaps in some act of ritual humiliation. Martin fully expected his report to result in the arrest and prosecution of the culprits, but the state attorney summarily dismissed him and did absolutely nothing. Was the Society again at work or were there larger forces involved in the cover-up? Or was it simply the fact that no one, aside from a few nosy outsiders, really gave a damn?

If the Princess and her lover had hoped to hit it big by rubbing out the old man, the scheme was a total bust. They turned to more mundane crime but had no success with that either. In 1930, authorities nabbed Terecita, Duran and nephew George for a string of house robberies. Georgie testified against his aunt and her boyfriend. After a five month stretch, Terecita came back to Taos, where she earned a living by fortune telling or, perhaps more to the point, as a bruja, or witch (Romancito). This landed her into trouble twenty years later when she was busted trying to fleece a couple in a curse-extortion scheme. Terecita Ferguson, the love of Manby’s life, died in 1979. She and Carmen Duran had long since drifted apart, but they kept their secrets. He passed away eight years earlier, also in Taos.

In the 1950s, Manby’s mansion, later Thorne House, became the Taos Center for the Arts and remains so today. Perhaps to no surprise, there are those who believe it to be haunted by Manby’s ghost. If so, he remains a very unhappy camper. One witness described his apparition as “a vile presence, filled with evil intent and malevolence” (Weigle, 216).

Manby was a complicated fellow: part Bond villain, part Western bad man, part ruthless gangster, and part cult leader. While he was architect of his success and his ruin, his story is not without an element of tragedy, and no shortage of mystery. Perhaps the most fitting epitaph for Manby and his strange career appeared in an editorial in the Santa Fe New Mexican which read: “One cannot help believing something has been going on in Taos which when revealed will astound the world” (Brandon, 149). If so, the secret is still intact.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albuquerque, New Mexico, City Directory, 1918.

Anderson, George Baker. “The Conquest of the Desert,” Out West, Vol. 25, #1 (1906), 112-113.

Brandon, Jim. Weird America: A Guide to Places of Mystery in the United States. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1978.

Bunker, Dr. Robert J. “Santa Muerte: Inspired and Ritualistic Killings.”

http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/law-enforcement-

bulletin/2013/february/santa-muerte-inspired-and-ritualistic-killings-part-1-of-3 (21 Jan. 2024).

Downard, James Shelby. The Carnivals of Life and Death. Los Angeles: Feral House, 2006.

“Extortion and Intimidation – Manby, Now Dead Is Accused of Being Head Of Sub Rosa Society.” The Huntsville Daily Times, March 18 1930.

“Murder and the Mystic Mine.” Strange Company: A Walk on the Weird Side of

History. http://strangeco.blogspot.com/2013/06/murder-and-mystic-mine.html (20 Jan. 2014)

Peters, James S. Headless in Taos: The Dark Fated Tale of Arthur Rochford Manby. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2012.

Records of the Secret Intelligence Service, File HD3/139, The National Archives, UK.

Report and Opinions of the Attorney General of New Mexico, 1912-1913. Santa Fe: The New Mexico Printing Co., 1914.

Romancito, Rick. “Lumina Gallery Plans Last Show.” The Taos News, 21 Aug. 2009.

Spence, Richard. “Basil Zaharoff: Man of Mystery,” New Dawn, # 134 (Sept.-Oct. 2012), 65-72.

___________. Secret Agent 666: Aleister Crowley, British Intelligence and the

Occult. Los Angeles: Feral House (2008).

“Taos County Early Deaths.” http://nmahgp.genealogyvillage.com//taos/early_deathrecords.htm (20 Jan. 2014).

“Thorne, Dr. Victor Corse.” http://thorn.pair.com/williamthorne1/d8480.htm#P8480. (20

Jan. 2014)

U. S. Census, 1890, 1900, 1910, 1920.

U. S. Congress, Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for 1903, Pt. III. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1903.

Wallace, Inez, “The Strange Death of Mysteriuos Mr. Manby,” The American Weekly (1943).

Waters, Frank. To Possess the Land: A Biography of Arthur Rochford Manby. Athens. Ohio: Swallow Press, 1973.

Weigle, Marta and White, Peter. The Lore of New Mexico. Santa Fe: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 2003.