In an effort to expand my understanding of the film-making of Dario Argento, last evening I watched an Argento-produced-and-written film called The Church (or La Chiesa). It was directed by Michele Soavi, who has been a long-time assistant to Argento, and who is noted for taking inspiration from Sergei Eisenstein and Orson Welles – in addition to his mentor Argento.

The film is considered by some to be a strong example in the Italian ‘Giallo’ genre of film-making in which Argento excels. Giallo is somewhat like a ‘film noir’ and represents a collection of films (Gialli) which encompass “historical horrors, crime dramas, and mystery thrillers”. The name derives from the yellow covers of Mussolini-era Italian pulp crime publications which were domestically produced following the censorship of similar foreign texts in fascist Italy.

Ostensibly, the 1989 film is about the massacre and “savage witch hunt” of a 13th century village of European satan worshipers by a merciless band of Teutonic Knights. The slain villagers (some of whom bear a cross-like stigmata on their feet) are dumped in a mass grave which is consecrated with a large cross. A Gothic cathedral is then built on top of the mass grave to seal the presumed demon which cursed the townsfolk. The remaining story takes place in the ‘present day’ and deals with the unsealing and escape of the evil force which has been kept beneath the church. I’ll not offer a further summary but suffice to say it kind of comes across as a cheesy Ghostbusters meets The Exorcist meets The Keep mishmash.

Having previously noted that the films of John Milius may complement a ‘propaganda dialectic’ benefiting Russia; I was already familiar with the notion that the raiders who kill the young Conan’s family in the film Conan the Barbarian (1982) came with inspiration from the Teutonic Knights of the Soviet propagandist Sergei Eisenstein’s “quintessential anti-fascist film”: Alexander Nevsky (1938). In addition, it is observed that scenes in the Milius-written Apocalypse Now (1979) took their inspiration from Eiseinstein’s Strike (1925), which is about the Bolshevik Revolution. It is therefore observed that “sources of Milius’ inspiration subvert his reputation as a hyper-conservative filmmaker”.

Milus’ continued high-level involvement in groups which have been apparently subverted by Russia such as the National Rifle Association (NRA), Gracie Jiu Jitsu-driven Mixed Martial Arts (MMA), and the Hollywood legacy of Orson Welles – seem to support an assertion that despite his anti-Communist and right-wing masculinist positioning, there is strong evidence that Milius is quite proximate to the promotion of Russian ‘cultural warfare’ through his art, networks, and other productions.

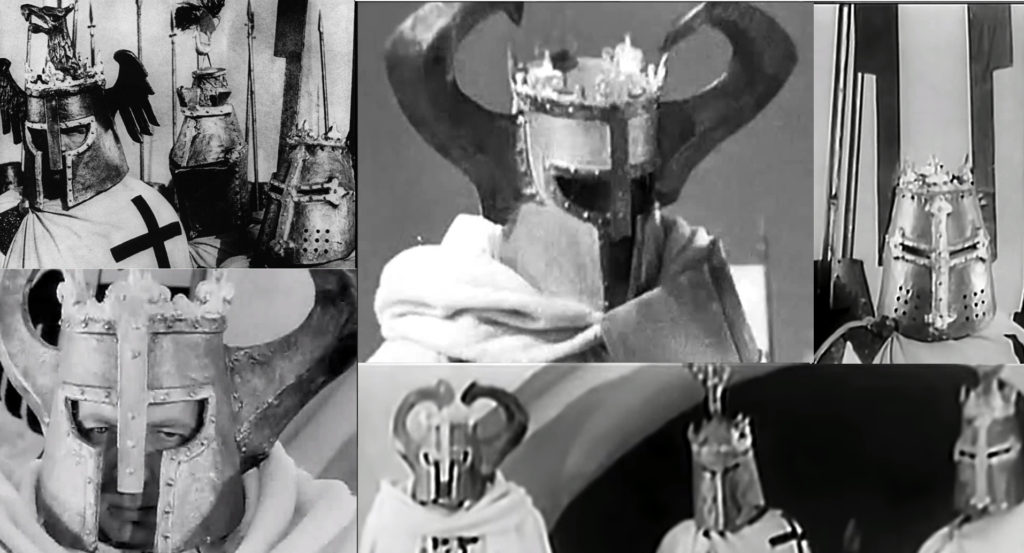

Eisenstein’s portrayal of the ‘Knights Teutonic’ in Alexander Nevsky had a specifically anti-Nazi flavor; with the costumes being embellished with Swastika-like symbols which were not used by the actual knights. The helmets worn by Eisenstein’s characters were based off of German helmets in WWI. Further, the film is seen as imbued with a Marxist political philosophy which laments capitalism and promotes the proletariat. (Ironically this ignores the role of Tsarist emigres in promotion of Theosophical doctrines in Germany and the adoption of the Swastika in Germany as the result of Russian influence.)

Nevsky was a celebrated figure in 13th century Russia for his defeat of Swedish Catholic armies and the Teutonic Knights on several occasions, including most specifically “The Battle of the Ice”, on April 5, 1242. “The Battle of the Ice served as inspiration to Soviet soldiers 700 years later when the Nazis launched Operation Barbarossa against Russia in 1941.”

It is seemingly within this historical context that the film served as effective Stalinist propaganda; despite the temporary shelving of the film and hypocritical abandonment of anti-fascist efforts by the Soviet Comintern propaganda machine following the contemporaneous Molotov-Ribbentrop pact alliance of 1938 with the Nazis.

The Church makes no effort to hide the parallels with Nazis, in the film, the knights are described as:

“A military religious order that defended the pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land at the time of the crusades. They later took over half of Europe – their cruelty became legendary. For instance, when they laid siege to a village, they would surround it with hanging corpses to terrorize the townspeople. They appealed a lot to the Nazis. Hitler drew his inspiration from them when he founded the SS. The Iron Cross – his favorite decoration – was modeled on the Black Cross of the Teutonic Knights”. (@21:50)

The history of Alexander Nevsky also makes mention of pagans aligning with the Eastern Orthodox Christians to repel the Catholic Teutonic Knights. (Anti-Catholicism is a common theme in Russian narratives, going back to at least the time of the prophecy of Third Rome, Ivan the Terrible and Dracula.) Indeed, it is perhaps within this context of the apparently paganistic villagers of 13th century Europe at odds with the Catholic Church that we might see a historical agreement that (in this example at least) brings modern occult film-making into alignment with Russian propaganda narratives. The ‘satanic’ villagers are made sympathetic, while the Teutonic Knights and the parochial Church are made into negative figures in The Church.

This observation continues to provide a rational basis for the notion that the conspiracy theories which surrounded the death of Anthony Bourdain are illuminated by a clear Communist propaganda legacy and connections to ‘dualistic’ Russian occultism, which may show evidence they are the artifacts/’fruits’ of a propaganda strategy. Anti-fascism in Soviet propaganda is seen to have evolved in the post WW2-years as a communication strategy directed at the Catholic Church, the US, Ukraine, and other various ‘enemies’ of the Russian state; much like how US propaganda was repurposed from targeting Nazis to targeting Soviets in the post-WW2 era. In the USSR, anti-Nazism/anti-fascism was one of the most useful ideological tools, and has continued to be under Putin.

The linking of the Catholic Church to Nazi war crimes was one of the biggest active measures Stalin undertook in the post-war years. This was described in detail in the essential book: Disinformation. The setting of the cathedral in Argento’s The Church, which is built on a mass grave of pagan martyrs killed by the openly Nazi-analogues – the Teutonic Knights – seems to be a commentary playing off of proven Soviet propaganda about Catholic cooperation with the Nazis in the Holocaust; given the film’s openly Communist creator and blatant influences from Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (a film said to be “100% [Russian] propaganda“).

Yellow (Giallo) by the way formed the basis for the ‘art propaganda’ of Wassily Kandinsky (see ‘The Yellow Sound’). Kandinsky was the director of the 1920’s-era Soviet ‘Institute of Artistic Culture’ and ‘Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences’, and included responsibility for film and also establishment of a ‘Plan for the Physico-Psychological Department of the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences’. He moved to Germany where he was embedded in the Marxist Bauhaus movement, and then ultimately France where he remained influential as an artist – first welcomed to Paris by Andre Breton, of the Sur des Independantes and author of ‘The Surrealist Manifesto’; and who had collaborated with Leon Trotsky and Diego Rivera on a manifesto for an ‘Independent Revolutionary Art’. Kandinsky explored paganism, was an antisemiticTheosophist, and in addition was the uncle of the notorious Russian spy Alexander Kojeve, who was a great influence on Breton and the Surrealist movement. Breton and other figures close to these men who specialized in dialectics (e.g. Claude Levi Strauss) were brought into the US during WW2 by Orson Welles’ Russian spy mentor Louis Dolivet in conjunction with the known spy Noel Field. Herein we might find a connection which links this propaganda theme with an overall intelligence strategy. Maybe Giallo means something within the context of the history of the color yellow in Russian art and communist resistance to fascism.